Introduction To Linux Terminal

1.1.The magic of Linux Terminal.

The Linux shell exists since Linux invented and it is still one of the most powerful ways for a user to interact with a system. There are thousands of different Linux distributions out there but if you look all of them from the command line perspective you will find out that all of them are almost the same. The Linux Terminal is fast, light, fully customizable, can be accessed remotely and so much more.

For most of the user at the beginning Linux terminal is just a black window that seems a bit unfriendly but after you get used to it you will love it.

I use Ubuntu on all my examples presented here but the magic of Linux Terminal is that you can use your favorite Linux distribution and still be able to follow.

There are several terminal instances running at the same time in Linux O.S. and most of the times you can access them by using key combinations. In Ubuntu you can use ctrl+alt+F1 to access the first command line instance ctrl+alt+F2 for the second and so on until the 6th. with ctrl+alt+F7 you can access the Graphic User Interface. From there you can open as many terminal emulators as you wish. those terminals can be started from the menu of the O.S. or in Ubuntu you can use ctrl+alt+t.

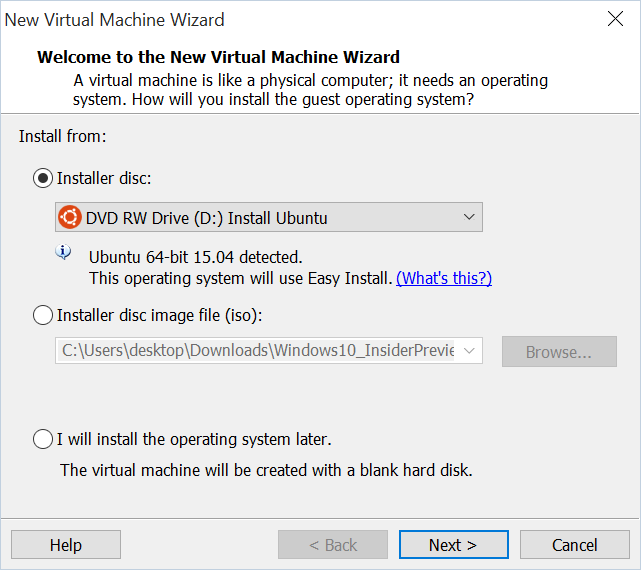

At that point i assume that you already have a running system and that you are able to open a terminal. If not then now it’s a good time to install a Linux system. You can either use a physical machine or a virtual.

But let’s get started!

1.2.Who am I? Where am I? what time is it???

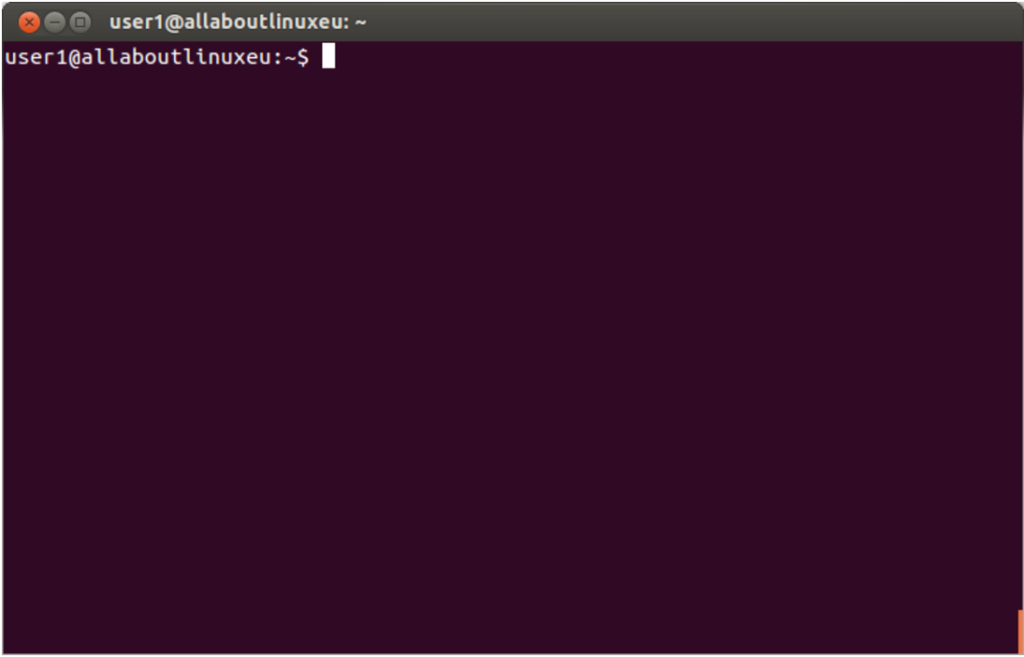

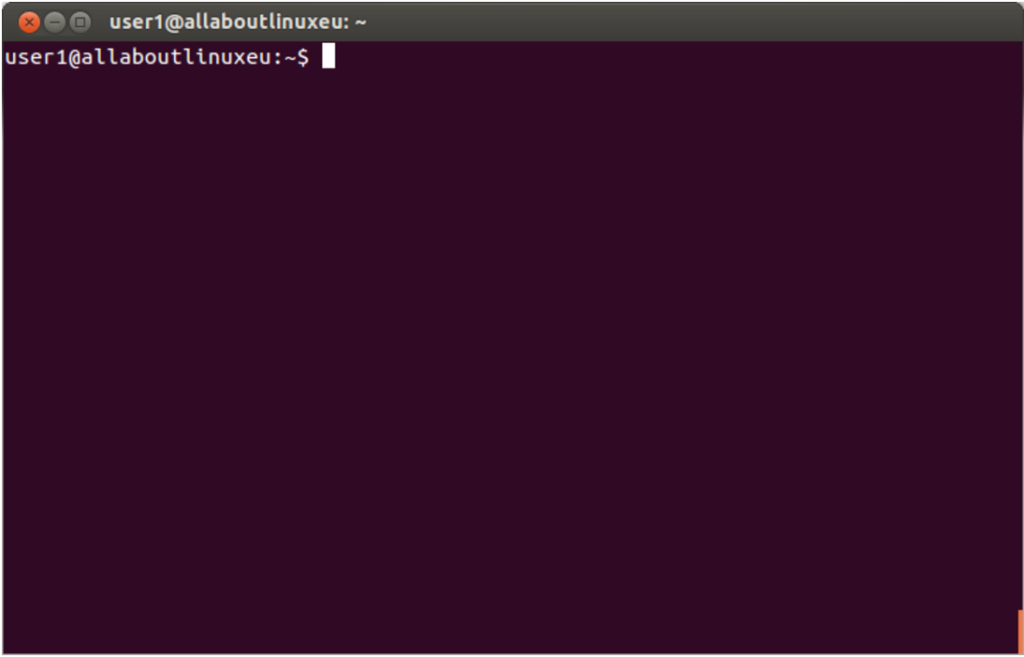

A Linux terminal emulator in Ubuntu is look like the image 1.1. Even without giving any commands you are still able to get some information out of this.

Image 1.1

This is what you get

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

user1: is the user-name of the current user

@: the at sign between user-name and computer-name

allaboutlinuxeu: is the computer-name or host-name

So altogether it says that user1 is connected to allaboutlinuxeu

the “:” indicates that the disk path is starting here.

the “~” indicates that I am currently in my home directory

the “$” indicates that I am logged in as normal user (if i logged in as root this symbol will change to “#”)

Note! This string user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ is not standard. Other Linux distribution might give less or more info. You can also customize that to fit your need but we will check that on a next chapter.

Let’s start with first question: Who am I?

At that point i want to mention that all text with gray background are commands or outputs from a terminal.

So now just type “whoami”

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ whoami

user1

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

After “$” you can type the command “whoami” and in the next line is coming the output of that command and then the Shell is going back to idle and it is just waiting for the next command. So I have successfully verify that I am “user1”.

But where am I? go ahead and type “pwd”

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ pwd

/home/user1

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

pwd stands for: Print current/Working Directory. I will not go deep into the file structure on a Linux machine right now but I will explain that later. for now, I know that “I am at /home/user1”.

And what about time, date, year? for that just type “date”

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ date

Tue Jul 11 23:18:09 UTC 2017

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

This output is pretty much self explained so i will not go any farther with that.

At any point you want to quit a terminal then you just need to type “exit”.

1.2.What is a Linux command?

A Linux command can be a single word following by some parameters some files or Directories or even some variable and inputs from user. We already went through some basic single word commands like whoami, pwd and date. But how can the O.S. understands what to do?

Most of the commands are actually small binaries (small programs) that was installed in your computer during the O.S. installation process. The binary whoami for example is in the directory /usr/bin . Normally in order to execute that binary you need to provide the full path. In that case /usr/bin/whoami . Try that:

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ /usr/bin/whoami

user1

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

As you can see the output is exactly the same since in both cases the same binary executed.

But how the system knows where to look for those binaries?

There are a few directories that contain binaries and and the O.S. is searching in those to check if a command provided in the terminal has a binary in those directories. If you want to see the list of those directories type the following command:

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

This is the full list of directories that the O.S. is looking for binaries for the current user.

Tip: The $PATH can also be modified to include or exclude some paths.

Since the /usr/bin is in that list the O.S. is executing binaries within that directory even without the /usr/bin so in that case only the command whoami is enough. This might be a bit confusing right now but it will be more clear later on.

1.3 The Main Linux Directories.

Linux have a hierarchical directory structure like the most Operating Systems. This system is a like a tree and it has a root directory that includes everything then there are some directories and files under that:

/

├── bin

├── boot

├── cdrom

├── dev

├── etc

├── home

├── lib

├── lib64

├── lost+found

├── media

├── mnt

├── opt

├── proc

├── root

├── run

├── sbin

├── srv

├── sys

├── tmp

├── usr

└── var

├── backups

├── cache

├── crash

├── lib

├── local

├── lock -> /run/lock

├── log

├── mail

├── metrics

├── opt

├── run -> /run

├── spool

└── tmp

In that example i have only expanded the subdirectories in /var and only in 1 level. There are many more subdirectories but the list wouldn’t easily fit here.

Let’s take a brief look on the main directories in Ubuntu.

/bin this is the first in the list and contains binaries that system needs to boot but many of those are also usable by users like the date command we used before.

/boot that is maybe the most important directory in a linux system. it contains the kernel (this is the heart of a linux O.S.) and important information for booting the system.

/dev here is a list of devices that the O.S. can access like hard drives partitions cd roms serial ports etc.

/etc one of the core directories of the system since it contains all the configurations of the system, scripts that are running during the boot usernames groups almost everything you can imagine that can be configured in a system.

/home this contains the home directories for each user and users can store their files and directories here.

/lib this is the library directory that is used by programs

/lost+found In case of an abnormal shutdown or if something is going wrong into your file system the O.S. will try to recover files and place them into that directory. Generally if this directory is empty is a good sign!

/media USB disks, USB sticks, CD-ROMS and other removable devices are mounted inside that directory. (that is not true for all Linux O.S.)

/mnt Generally that directory is empty but this is good place if you want to manually add shared/network directory or manually mount a device

/opt that is also kinda new in Linux and it is used to hold “optional Software” software that users install or anything that is not part of the main O.S. in the past that directory was under /usr/local and some programs are still prefer that directory.

/proc that is an interesting Directory since it hold files that used mainly by the system to identify hardware parts but in most cases those files are human readable and you can get some interesting information out of that.

/root that is the home directory for user root. This is a special user that have permissions to do anything in a Linux machine

/sbin this one is like /bin and hold some binaries that can be executed by root or any super user.

/tmp A temporary directory that programs are storing temporary info while programs executed in your system.

/usr This folder contains most of the binaries used by users and sometimes by system. There are many interesting subdirectories in this one.

/var That directory holds dynamically changed files like log files, databases and generally is the most active directory in the system.

1.4 Navigate into Linux File system.

the main command to jump from one directory to another is the “cd” and this one stands for “Change Directory”. Let’s navigate to the root. This is the main directory that holds all others and it is represented by the “/” slash symbol.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ cd /

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:/$

As you can see the “~” tilde symbol that represents the home directory of the user changed to “/”

Tip: at anytime if you want to check the path to the current working directory you can issue the “pwd” command.

Now that we are at the root of our file system we can navigate to any directory that we have permissions to read. We will talk about permissions in a later chapter. let’s go to “usr” directory and from there inside the “games” directory. This can be done step by step like:

user1@allaboutlinux:/$ cd usr

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr$ cd games

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr/games$

or with one command like:

user1@allaboutlinux:/$ cd usr/games

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr/games$

You may have already noticed that the directories are separated by “/” and also the command prompt string changed from “user1@allaboutlinux:/$” to “user1@allaboutlinux:/usr/games$” in that way you can always check the current working directory that starts after the “:”

In order to move back one directory then we can use the command “cd ..”:

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr/games$ cd ..

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr$

The “..” two dots are standing for the parent directory while the “.” one dot stands for the current directory there is no point to change to current directory but that is important on some other occasions.

1.4.1 Absolute path vs Relative path.

The absolute path.

Every directory or file in our file system have its own unique path. This address starts from “/” and ends at the directory or the file that we want to reach. For example if we want to play gnome-sudoku we need to know the path to that game.

Note! Ubuntu and some other debian based Linux are coming with that game. This may not be available in other Linux distributions.

The absolute path for that game is /usr/games/gnome-sudoku

As you can see that path starts with “/” following by some subdirectories and ends at the filename. Some other O.S. used to have an extension to every file and with that the file is identified. In Linux, extensions are not mandatory. So now if i want to play that game all i have to do is to provide the absolute path to that game and i can do that from any location. It doesn’t matter if i am in /var or in /home/user1. Since i am providing the absolute path the system will just go there and execute the file. that is the meaning of the absolute path.

let’s have some fun:

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr$ /usr/games/gnome-sudoku

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr$

At that point a new window will open and sudoku will run. Once you close the window the command line will become again available.

Relative path.

There is also another way to navigate through file system by providing the relative path. instead of starting from “/” you can start from any other location and that path will be relative to your current working directory. Right now you are at “/usr” and if you want to start again the same game that is in a subdirectory of usr then you need to provide the relative path from “/usr” to the executable. as we said before the “.” one dot stands for the current directory. So if i am in “/usr” and type “.” then in essence I am saying /usr/ and from there i can continue like “./games/gnome-sudoku” or if i was already inside the games directory (so my current working directory was /usr/games/) then i would be able to execute the same game by typing ./gnome-sudoku

It might sound a bit complicated at that point but we will see many examples of that later on and it will become much more clear. But for now just remember that when i’m providing the full path starting from root “/” to the file or directory i’m using the absolute path and when I am providing a path related to my current working directory I am using a Relative path. There is no right and wrong way to do something we just use whatever is more convenient.

1.5 List the contents of a directory “ls”

Let’s list the contents in the root directory. For that you will need the ls command.

ls stands for “list”

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:/$ ls

bin dev initrd.img lib64 mnt root srv usr vmlinuz.old

boot etc initrd.img.old lost+found opt run sys var

cdrom home lib media proc sbin tmp

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:/$

Those 2 commands are the most basic in order to navigate to a directory and list all the files in that directory. if we want for example to check the contents of /usr then we can first go inside /usr and then list the contents.

user1@allaboutlinux:/$ cd usr

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr$ ls

bin games include lib local locale sbin share src

user1@allaboutlinux:/usr$

“ls” by default is listing the contents of the current working directory but you can also provide the path of the directory that you want to list the contents and run the command from everywhere without going directly into the specific directory. In the same scenario where I am in root directory “/” and i was to check the contents of /usr instead of moving in i run directly the “ls” command and providing the absolute path of the directory.

user1@allaboutlinux:/$ ls /usr/

bin games include lib local locale sbin share src

user1@allaboutlinux:/$

In this directory you can see the full list of files and directories that you have in your Linux but as a normal user you do not have access to all of them. Every user have his own directory where he/she have full control to read write and execute. Now its time to go back to owr home directory and create a subdirectory and a file inside that directory. there are many ways to do that but the easiest is by typing “cd ~/” that is equal to “cd /home/user1” where user1 is the name of current user.

method 1:

user1@allaboutlinux:/$ cd ~/

user1@allaboutlinux:~$

method 2:

user1@allaboutlinux:/$ cd /home/user1/

user1@allaboutlinux:~$

1.6 Creating and deleting files and directories

Now we are in our Home directory. With the following command we can create a directory named “working_directory”

user1@allaboutlinux:~$ mkdir working_directory

user1@allaboutlinux:~$

Tip: By default this command will not return any output. in case that there is a problem during creating the directory an output will be generated and you will be able to check what went wrong. A common issue is when you are trying to create a sub-directory inside a directory that you don’t have write permission. We will talk about permissions in a next chapter.

Note you should not use “space” in files or directories names. the command “mkdir working directory” will actually create 2 directories one named “working” and one named “directory”

ok now that we have a test directory we can go in and create a file with name test_file. again here I am using an underscore otherwise the system will generate 2 file one named test and one named file. the command to create an empty file is the “touch”. so lets do that.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ cd working_directory/

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$ touch test_file

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$

now lets list the contents of this directory

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$ ls

test_file

Great so we have our first file inside our first directory. Now lets move on and delete this file. The command that we need to use is the “rm” which stands for remove and it can be used for both files and directories. lets delete the file by issuing the “rm” followed by the file name and list the contents of directory to make sure that the file is deleted.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$ rm test_file

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$ ls

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$

Note Linux will never ask by default for a confirmation when you are deleting a file and will not produce any output if the operation was successful. It will always assume that you know what are you doing. You also need to have in mind that the file is not going into a trash can or anything similar. So you should say good-bye to your file for good.

Now lets try to remove the directory that we created before. We will need to navigate to the parent directory and then issue the rm command again followed by the directory name. But since this is a directory we need to use the option “-d”. The -d is saying to rm to remove an empty directory. so lets do that.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~/working_directory$ cd ..

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ rm -d working_directory/

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$

now we need to mention 2 more parameters for the rm command is the -r that stands for Recursive and the -f that stands for Force.

if you combine those 2 together then you can remove a directory and its contents no matter how many sub directories and files are listed inside.

So the command will look like the following.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ rm -rf working_directory/

1.7. Users and Groups

In a Linux system you can create as many users as you need. Those users can be local or network users if you are running a NIS authentication. For now we will talk about local users.

Each user in a Linux system has its own Directory where he/she has full permissions and as we already said the short path symbol for that is the “~”

so in order to navigate into this directory all you have to do is to issue the following command:

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:/$ cd ~

In there users can store their personal files and also change the configuration files so they can customize their terminals. those files are not visible by default since they are hidden. but you can see them if you type the “ls” command following by the -a parameter.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ ls -a

. .cache Downloads Music Videos

.. .config examples.desktop Pictures .Xauthority

.bash_history Desktop .gconf .profile .xsession-errors

.bash_logout .dmrc .ICEauthority Public

.bashrc Documents .local Templates

The names of all hidden files and directories starts with a “.”. lets check a few of the most interesting files.

.bash_history

in this file the system stores all the commands that you are typing in a terminal and this is a great source to check what you have done so far. this is a plain text file and you can check the contents of it by using the “cat” command.

user1@allaboutlinuxeu:~$ cat .bash_history

ls ~

cd ~

ll

ls ~

ls -a ~

ls -a

Another way to check your history is by simply issuing the “history” command that will give the same results.

.bash_logout

This is a script that is running when a user is logging off from his/her account and by default it is clearing the screen to increase privacy. This files can be adjusted so you can perform some extra actions upon log off. One of my favorites is to back up some important directories to a share drive. We will talk about modifing those files in another chapter.

.profile

This is one is executed once the user is logging in and its a great place to define config files for your account. In Ubuntu for example it defines the basic account config file and the $PATH that we talked already in a previous Chapter.

And last but not least is the .bashrc file. This is maybe the most important config file for your account and we will spend a lot of time on that later on.

The usergroups in a Linux system are logical combinations of users. Users can be part of many groups. Basically this is a great way to categorize users and provide them permissions on specific directories or files.

At the end we need to say a few words about “root” user. This user exists on all Linux machines and it is a special user that have permissions to access and modify everything in the system. You should avoid using this user for everyday work but when everything collapse then you know that you can count on this user. Normally in a production environment only the Linux administrators have access to this account.

1.8 Permissions on Files and Directories

To be continue…

Stay tuned 😉

Recent Comments